Originally Posted by

Larry Williams

Robby,

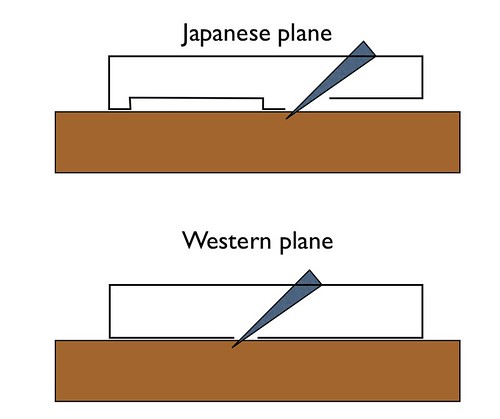

A tight mouth can help reduce tear out but tear out isn't necessarily related to spring back.

I think tear out happens when the resistance to the cut is greater than the strength of the fibers or when the lifting action of the cutting geometry is greater than the strength of the fibers. I still have a lot to learn. One thing I have learned is that planes, especially 18th Century British wooden planes, are highly evolved and incredibly sophisticated. The tools have to be as sophisticated as the products they produce; Chippendale, Sheraton and others didn't make the masterpieces they did with stone axes.

Another important thing I've learned is not to try to redesign or change the traditional designs with out really studying purpose of the features I'm attempting to improve and the ramifications. Leonard Bailey, Justus Traut and the other 19th Century design contractors for Stanley were pretty bright and talented guys. Still, when they translated wooden plane designs to metal they missed a lot. They had a lot of years and money to improve and refine those iron planes but in so many cases they never got it right. I think a lot was lost in the translation.

I know I'm not nearly as smart as collective knowledge of all those that worked before me. I'm still trying to figure out what all they knew. The idea that I might make some big improvement has vanished. At this point, I think it would be arrogant to think I'll improve anything. I just want to figure out all I can from the evidence the early plane makers left behind.

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote